Given recent downward moves in both stock and bond markets and the many fears that have dominated financial headlines in 2023 (see our Q3 commentary “Yet Again, the Sky Does Not Fall”), it would be understandable if investors forgot that this has actually been a good year for equity investors. Despite a downward move of almost 7% since hitting an intra-year high on July 31, the broad US stock market has returned 12.4% in 2023, as of this writing. Foreign stocks have also produced positive, albeit much lower, returns this year. Investment grade bonds, normally far less volatile than stocks, have been a different story. After posting strong returns in the first quarter, the widely followed Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index has lost 6.0% since April 4, the result of a big upward surge in long-term interest rates, and now shows a -2.4% return on the year. Longer dated bonds have fared worse, with the US Treasury 10 year note losing over 10% since the spring.

While we can’t know what path interest rates will take (bond prices and interest rates have an inverse mathematical relationship), we can nevertheless implement a sound strategy to take advantage of the new rate environment going forward. A study of past Federal Reserve interest rate policy cycles provides a strong basis for the development of such a bond strategy.

The current interest rate cycle began in March of 2022, when the Fed belatedly began raising short term interest rates to combat inflation. At that time, the Fed also ended its program called Quantitative Easing, which refers to the purchase of long maturity bonds with newly created money, a policy intended to lower long-term interest rates. Since then, interest rates have risen rapidly, though more rapidly in short maturities than in long ones. The greater increase in short-term interest rates has resulted in an “inverted yield curve”, which refers to an environment where short rates exceed long ones. This resulted in part from the Fed’s aggressive hiking of overnight rates, and partly from fears of recession, which decreased demand for long-term borrowing by businesses and households.

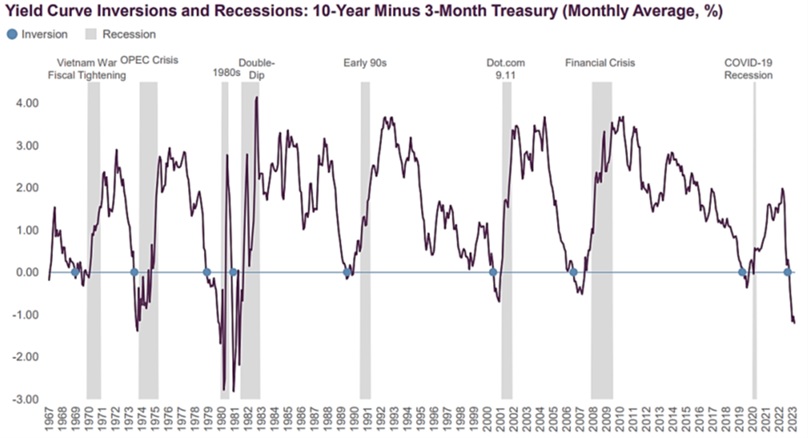

Graph 1 shows inverted yield curves over the last several decades, which we can see preceded each of the last seven recessions.

Graph 1

Source: Guggenheim

To develop a cogent strategy for bond investing in the new interest rate environment, we need to bear in mind that longer dated bonds have more price volatility than shorter dated bonds (and CDs and Treasury bills), and are therefore more risky. This is why longer dated bonds have experienced greater losses than shorter ones this year, even though short rates have risen more. We must also keep in mind that we cannot know the future direction of interest rates with certainty, though we do know that further rate increases will cause bond losses, and rate declines will result in bond price gains.

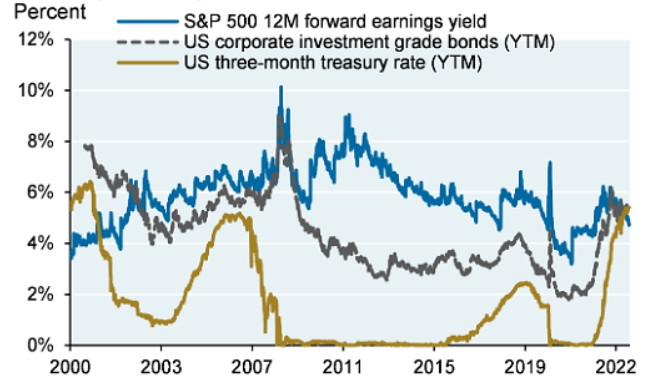

Graph 2 illustrates the recent market yield convergence, during which lower risk 3 month Treasury bill yields have risen to equal (or exceed) the yields of much riskier investments, in this case the earnings yield on US stocks, and the yield on longer maturity high grade corporate bonds. This illustrates that short, low risk investments now offer higher yields than some riskier investments.

Graph 2

Source: JPM, BBG

With this as context, we have fielded the same question from many clients, which essentially is: “Why shouldn’t I park cash in short maturity CDs or T-bills where I can earn 5.5% (or more), hide out for a bit, and earn more than the yield on longer dated bonds while taking less risk?”. This is an eminently logical question –

Why not earn more yield while accepting less risk?

While this question is a good one, history has shown that high short-term yields (often when the yield curve is inverted) near the end of a Fed tightening cycle are a siren song. The reason may not be obvious, but it is nevertheless intuitive. Once the Fed is done tightening, it tends to leave rates unchanged for a while before proceeding to lower rates in response to a weakening economy which, to some extent, the higher rates it introduced contributed. As a result, investors in short, safe investments such as CDs and T-bills enjoy their yields for only a short period of time, then must reinvest at lower rates when the investments mature. In contrast, longer dated bonds typically experience price appreciation in anticipation of lower future interest rates, meaning that investors in longer dated bonds earn not only the bond yield, but also capital gains (which investors sheltering in shorter investments do not receive to nearly the same degree). The historic result has typically been that investors who take more risk in longer bonds at this point in a rate cycle get greater returns, despite investing at lower yields.

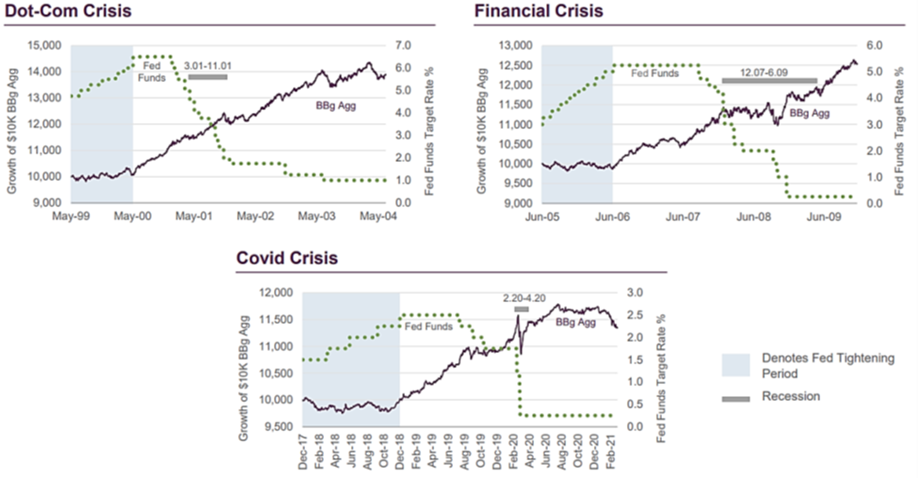

Graph 3 shows strong returns for the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index beginning when the Fed finished recent tightening cycles, when the yield curve was also inverted, in each case also prior to recessions.

Graph 3

Source: Guggenheim

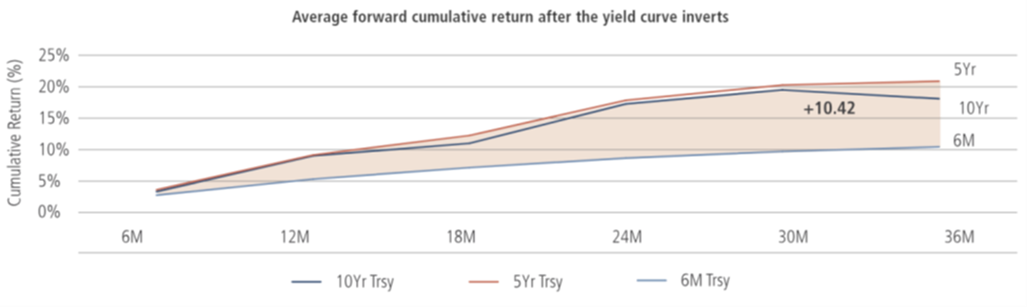

Graph 4 quantifies the advantage of investing in longer maturity bonds over the past four interest rate cycles, showing materially higher total returns accruing to longer securities over three years after Fed tightening ends (the best performing maturity has been 5 year bonds).

Graph 4

Source: Neuberger Berman

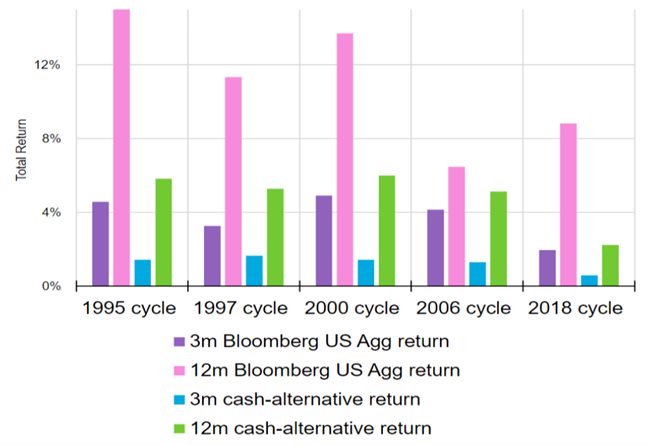

Graph 5 illustrates that even over short timeframes (in this case just three and twelve months) longer dated bonds have materially outperformed higher yielding cash investments.

Graph 5

Source: Blackrock, Morningstar

In investing, there is always risk, and there is no assurance that any strategy, no matter how well reasoned, will ultimately prove successful. In this case, the argument I lay out for shunning cash in favor of intermediate bonds might not work: one scenario in which it would not work might be if inflation turned up again, and as a result interest rates of all maturities rose considerably from current levels. That would lead to losses on intermediate bonds. Nevertheless, with history as a guide and lacking a crystal ball, extending debt maturities at the likely end of a Fed tightening cycle when the yield curve is inverted, as several of our bond managers have done, is a sound strategy.

Thank you for your trust, and please contact a SFA team member with any questions, or to review the alignment of your portfolio with your personal circumstances.

The information contained within this letter is strictly for information purposes and should in no way be construed as investment advice or recommendations. Investment recommendations are made only to clients of Santa Fe Advisors, LLC on an individual basis. The views expressed in this document are those of Santa Fe Advisors as of the date of this letter. Our views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions and Santa Fe Advisors has no responsibility to update such views. This material is being furnished on a confidential basis, is not intended for public use or distribution, and is not to be reproduced or distributed to others without the prior consent of Santa Fe Advisors.

To Top

To Top