So far in 2025, the equity markets (and, to a significant extent, the US Treasury market) have been roiled by unexpected activity on the part of the new Administration. But the activity that has had the greatest effect on the financial markets – and which has dramatically increased market volatility – has been the imposition of a wide range of tariffs on almost all of America’s trading partners.

Because this has been the defining financial event of 2025 so far, we thought it would be useful to have a brief review of what a tariff is, and what its effect on the overall economy may be. There is a great deal that is still unknown regarding what tariffs will actually be imposed, as opposed to threatened for negotiating purposes, so the ultimate impact is still unknown.

Summary

Tariffs are likely to have a broad effect on the US economy, particularly if imposed as the Administration threatens. While the stated intention of the tariffs is to bring manufacturing back to the US, this is almost impossible to achieve in the short term and may be economically inefficient and costly in the long term, as many foreign countries can produce goods more cheaply than the US. Because of the interlinked nature of the global economy, costs are likely to rise for both manufacturers and consumers, which could lead to higher inflation, if not offset by lower economic activity. At the same time, consumption and employment are both expected to fall. Higher inflation, may, in turn, affect the Federal Reserve’s plans to cut US interest rates.

The negative effects on the economy, interest rates, consumption, corporate profits, and employment have resulted in a great deal of volatility and significant losses in the stock market since the so-called “liberation day” on April 2. In general, markets believe that these tariffs, if implemented, will have significantly negative effects, for reasons that are explained below.

What is a Tariff?

A tariff is simply a tax that is levied by a government on imported goods. It has the effect of making imported goods more expensive and, by extension, domestically produced goods more competitive. In the US, tariffs and other taxes are controlled by Congress under the Constitution, but Congress has passed laws allowing the President to impose tariffs for national security reasons. Because tariffs disproportionately affect consumers at lower economic levels, they are generally considered to be a regressive tax.

The Theory of Comparative Advantage

A hallmark of economic thought is the theory of comparative advantage, first laid out by David Ricardo in the 19th century. It states that nations should specialize in the areas of production that they can do most efficiently and to import those goods that they cannot manufacture as efficiently as others. If Italy can make loafers more cheaply than France, and France can make espadrilles more cheaply than Italy, then each of them should concentrate on doing what they do best. That way Italian and French citizens will have both loafers and espadrilles produced at the least possible cost.

However, the theory of comparative advantage depends on a low tariff or free trade environment. If the Italians have a high tariff on shoes, then it may make the cost of French espadrilles uncompetitive in Italy. And give Italian manufacturers the incentive to produce espadrilles themselves, even though the French can do it cheaper. Which means that instead of concentrating their manufacturing power on loafers, where they can be internationally competitive and make the most money, they are diverting some of their resources to making espadrilles for the domestic market. And if France does the same thing – imposes a tariff on shoes – then the Italians may not be able to sell loafers to French citizens, reducing their sales of the things that they do the best and increasing the sales of the things they don’t do well. That is a loss for both manufacturers and consumers.

You can see that this example runs counter to the widespread belief that protectionism always benefits domestic industry. In this case, Italian loafer makers could have, through economies of scale and natural comparative advantage, become the dominant makers of loafers for the entire world. Tariffs discouraged and in fact prevented them from doing so.

A History of Tariffs

At the founding of the United States, there was no income tax (which was not imposed until 1913). As a result, tariffs on imported goods represented the vast majority of government revenue. The precursor to the US Coast Guard, the Revenue Cutter Service, was founded in 1790 to enforce and collect import tariffs.

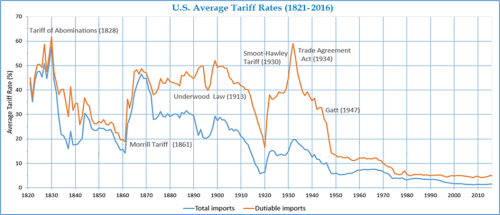

Many people are surprised to learn that for most of its history, including its greatest period of economic expansion, the US has had relatively high tariffs. Initially tariffs were set at 12.5%, but were doubled during the War of 1812 to support higher government spending. By 1820, tariffs averaged 40% in the US and this high rate continued until after the end of World War II. This protection for US industries corresponded to a period where the US economy was the fastest growing in the world.

Table 1

Source: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the US 1789-1945, US International Trade Commission, dataweb.usitc.gov

The protectionist stance grew directly out of a long-standing British policy called mercantilism, which was designed to promote the growth of British industry. British tariff policy was designed to ensure that manufactured goods were primarily or exclusively produced in Britain, while Britain’s colonies (most importantly America and India) were limited to the production of raw materials used in British manufacturing. This policy contributed to the massive growth of British industry during the 18th and 19th centuries. However, the tensions that it caused also led directly to the American Revolution, as American colonists resented the restrictions on their ability to develop independent industries and the requirement that all finished goods be purchased from Britain.

The effectiveness of the British tariffs, and the dominance of British industry, was reinforced by the overwhelming strength of the British Navy and the corresponding power of British corporations such as the East India Company.

Following World War II, in a period where international cooperation was strongly favored, organizations such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization were founded and had the general effect of dramatically reducing tariffs and promoting free trade around the world. It was believed that stronger multilateral trading relationships would be instrumental in reducing conflict and the risk of another global war, and this has largely been proven true until now.

Why wouldn’t protectionism work today? Well, the complex nature of many of today’s manufactured goods means that tariffs affect domestic producers almost as much as foreign ones. For example, Boeing and Ford both import a great deal of materials, both raw (aluminum) and finished (wiring harnesses, engine parts, and so forth) to assemble their products. Tariffs will therefore affect them as much as end consumers. This was not the case in the 18th and 19th centuries, when protectionism was an effective tool to develop domestic industries.

Tariff Policy and Industrial Impact

In a simple world, tariffs are a benefit to domestic industry because they raise the cost of imports. This may be regarded as a legitimate purpose in several instances. For example, a country that is trying to build up a certain industry may decide to use tariffs to temporarily protect that industry as it is getting off the ground and before it achieves economies of scale.

It is also possible that another country may be trying to compete by selling goods at unmatchable and uneconomic prices (such as through government subsidies) in order to drive domestic producers out of business. For example, at present Chinese automakers are the global leaders in electric cars, a position that is unlikely to change. In the absence of tariffs, the Chinese could elect to try to drive French automakers out of business by selling cars so cheaply that French manufacturers cannot compete. This might mean selling cars at a loss for a while, only to recoup the profits when competitors have been bankrupted and the market is no longer competitive. Tariffs are an accepted way of protecting domestic industries from such unfair competition.

Who Pays Tariffs?

This is not a simple question. Tariffs are imposed on the importer of goods. However, whether the importer or consumer ultimately bears the burden depends on the demand or pricing power of the company involved. For example, let’s say that the tariff on an imported Toyota is $10,000. The cost of producing a Toyota is, let’s say, the same as producing an equivalent Ford. So the cost should be the same without the tariff.

To sell a car in the US, Toyota has to pay the $10,000 and then has to decide whether to raise its price by $10,000 to cover the tariff. If it does, then buyers of Toyotas will pay an extra $10,000 and that will be a direct tax on the consumer paid to the US government. However, Toyota may decide that to remain competitive, it needs to absorb the tariff and keep its prices the same, effectively reducing its profits. In that case, the tax would be paid by Toyota. Commonly, there may be a mixed result where Toyota raises prices by a lesser amount (say, $5,000) and therefore the cost of the tariff is shared by the consumer and the producer.

A complicating factor is that if Toyota decides to raise its prices by the full $10,000 to cover the tariff, Ford may ALSO raise its prices, using the logic that if the cars are equivalent, they can make more money by charging more since the competing product is artificially more expensive. Let’s say that Ford raises its prices by $5,000, so its cars are still $5,000 cheaper than Toyotas but higher than they were. In that case, buyers of Toyotas will still be paying a $10,000 tax to the government, but buyers of Fords will also be paying a $5,000 tax. In this case, the tax is paid to Ford (in the form of higher prices) rather than to the government. So this is a direct transfer from the consumer to the producer, which is one of the common features of tariffs… they are bad for consumers and good for domestic producers, either through higher prices or reduced competition, often both.

Tariffs in Today’s World

As shown in Table 1, the world has been in a generally low-tariff environment since the end of World War II. The recent actions of the Trump Administration have raised US tariffs to their highest level in 90 years.

It is hard to predict what tariffs will in fact be imposed or deferred, since the Administration seems to change its mind about this on an almost daily basis. But let’s assume that the current 145% tax on Chinese goods (with reciprocal tariffs back from China) stay in place, and that most of the currently announced tariffs that have been deferred until July are ultimately imposed. Note that even the suspension has left a baseline of 10% tariffs in place, which is roughly double the rate in existence for most of the past 50 years.

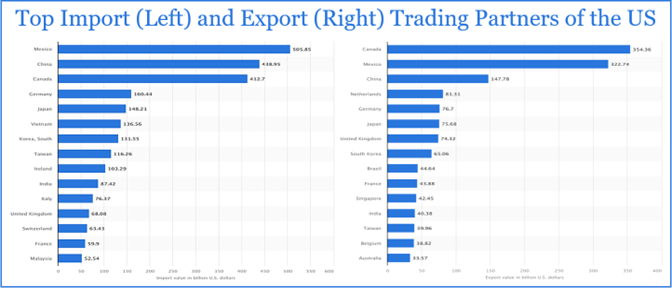

Table 2

Source: Statistica Research Service

Just looking at the US and China alone, this is one of the world’s largest trading relationships. The US imported nearly $440 billion worth of goods from China in 2024, second only to Mexico. China also ranked third in US exports in 2023, with $148 billion (behind Canada and Mexico). As a result of tariffs now over 100%, this trade relationship is likely to almost entirely shut down. Indeed, China announced yesterday a suspension of the delivery of all Boeing aircraft to Chinese airlines, even though the US announced an exemption from Chinese tariffs for certain technology gear.

In the short term, it is unlikely that US manufacturers will be able to pick up the slack in the various goods produced by China, leading to shortages of some goods. Moreover, Chinese exporters who are unable to sell their goods in the US are likely to turn to other markets, most notably Europe. This may result in a flood of goods hitting the European market as exporters seek to replace US consumption.

Implications for the US Economy

Despite Administration forecasts that the proposed tariffs will result in positive effects for the US economy, private and academic economists have an overwhelmingly negative view of these effects.

- Penn Wharton forecasts a significant decline in both consumption and wages, with a decline in consumption of up to 4.5% by 2030. Lower imports lead to lower foreign purchases of government debt. Lower consumption leads to a decline in real wages by 6.5% and overall production of 7.7% over the next 30 years.

- A study by Yale University predicts a short term rise of 2.9% in costs or roughly $4,700 per household, disproportionately affecting clothing and textiles, with a reduction in GDP of 1.1% and job losses of about 740,000 annually by the end of the year.

- A JP Morgan study expects tariffs to cause a 1-1.5% rise in personal consumption expenditures, mostly in the middle of the year, with real disposable income growth turning negative. As a result, they believe that there is a risk that real consumer spending will also contract. JP Morgan also expects automobile prices to increase by roughly 11%, with both foreign and domestic manufacturers raising prices.

- The nonpartisan Tax Foundation predicts a reduction in after-tax income of 1.3%, the equivalent of a tax increase of $1,300 on the average US household.

- Brokerage firm Edward Jones expects corporate margins to be squeezed as a result of higher import costs, along with a decline in real individual income. In general, Edward Jones expects higher costs and lower growth.

- Goldman Sachs predicts a net loss of roughly 400,000 US jobs. While manufacturing employment will increase by roughly 100,000 jobs due to the protective nature of the tariffs, it is likely that the increased costs of imports and their effects on other industries (e.g. retail) will cost nearly 500,000 jobs. The same Goldman Sachs report predicts a 45% chance of a recession with US GDP growth slowing to only 0.5% as a result of the tariffs.

Conclusion

While there is a long history of tariffs effectively promoting the growth of domestic manufacturing, as the Trump Administration claims is its goal, those successes came at a time when manufacturing processes were much simpler and less intertwined. It seems unlikely that the current proposed tariffs will result in positive economic effects in the US or globally.

Thank you for your trust, and please contact us if you have any questions, or would like to review the appropriateness of your portfolio risk.

The information contained within this letter is strictly for information purposes and should in no way be construed as investment advice or recommendations. Investment recommendations are made only to clients of Santa Fe Advisors, LLC on an individual basis. The views expressed in this document are those of Santa Fe Advisors as of the date of this letter. Our views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions and Santa Fe Advisors has no responsibility to update such views. This material is being furnished on a confidential basis, is not intended for public use or distribution, and is not to be reproduced or distributed to others without the prior consent of Santa Fe Advisors.

To Top

To Top